Market Update – Inflation Overshoots

Investment Update – Inflation Overshoots – 20th May 2022

Overview

The first quarter of 2022 was a volatile period for equity markets. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine caused extreme uncertainty, although there was some relief toward the end of the period, partly due to the fact that the conflict hadn’t escalated further. Meanwhile, lockdowns in parts of China reminded investors that we have not yet entirely moved on from the pandemic. These geopolitical challenges continue to impact supply chains, with the bottlenecks causing sharp price rises in input costs. Energy and food prices have been particularly affected. Ongoing market jitters centre around what impact these events will have on the global economy over the coming months.

Ukraine & Russia

As highlighted in our last report, Russia represents only 2% of global GDP and, other than via its commodity exports, it has limited interaction with the global economy. Our portfolios have minimal to zero direct exposure to Russia.

The biggest impact on financial markets and the global economy has therefore been the war induced spike in energy costs (oil & gas) and commodity costs (especially wheat, fertiliser, and nickel). Although the initial rise in prices rolled over toward the end of the quarter, wheat prices were still 33% higher and Brent oil up 43%.

Although we had previously highlighted input cost inflation as a significant issue in the second half of 2021 due to the impact of Covid on supply chains, the pressure has been exacerbated by events in Ukraine. Meanwhile, there has been no relief from the tightness in the labour market, especially in the US, which continues to cause upward pressure on wages.

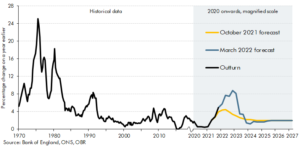

These effects are combining to apply upward pressure on general inflation and inflationary expectations. These pressures are not expected to ease in the near future. In the US the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is now reading 8.5% inflation year on year, with the UK at 9%. The UK Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) continues to project a continuation of the rise before an easing of inflation in 2023. The March projection suggests an increase in the peak (from October’s projection) but the expectation remains that inflation will ease, as follows:

UK CPI Inflation

It stands to reason that the recent spikes in energy and food prices will eventually fall out of the figures on the anniversary of the spike (in the first quarter of 2023), assuming those prices don’t continue to rise from current levels.

Inflation Overshoot

It is reasonable to ask the question – how did central banks allow this to happen? The reasons for the overshoot can be traced back to 2020 when the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) and other central banks were keen to generate more inflation in the financial system and so introduced flexible average inflation targeting. So, at the time the Fed fully intended that inflation would rise above 2%. However, this permissiveness coincided with a huge government spending package and supply chain difficulties – both related to the pandemic. In 2021, we were concerned that the Fed was still keen to pump money into the system despite the US economy returning to normal, with the post-lockdown bounce back in demand.

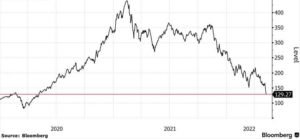

The excess liquidity in the economy was one factor that led to extreme distortions in the financial markets, such as the flow of money into the US technology sector. This overexuberance is now in reverse. You may recall we were tracking the Goldman Sachs Non Profitable Tech Index through lockdown. The chart now looks like this:

Goldman Sachs Non-Profitable Tech Index

The effect of all of this is that there is now a relatively urgent need for policy to take price pressure out of the system. The Fed is specifically targeting policies to address the labour market imbalance in the US where there are now twice as many job vacancies as there are unemployed.

At the most recent Fed meeting Chairman Jerome Powell said “inflation is much too high and we understand the hardship it is causing and we’re moving expeditiously to bring it back down.”

Interest Rates and Quantitative Easing (QE)

So the recent rises in interest rates will continue until the Fed feels it can bring inflation under control. In addition, the ‘Quantitative Easing’ (whereby central banks buy assets from the market to support the financial system) that has been in place since the 2007-8 financial crisis is now in reverse, which effectively means Quantitative Tightening (QT). Other central banks such as the Bank of England and the European Central Bank (ECB) are involved in QT too. This will present a headwind to economies, taking inflationary pressure out of the system, but also risking an uncomfortably sharp slowdown in growth.

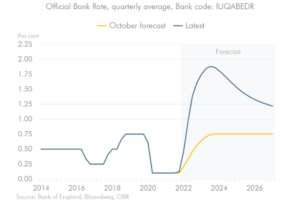

The trajectory of interest rates is likely to continue steadily. In the US, the Fed is likely to go further than it needs to in order to dampen inflation and is already projecting interest rate rises of 0.5% in both June and July. In Europe, the ECB is expected to begin to move rates up from July onwards. In the UK, in March the OBR projected the following sharp increase in interest rates, a higher peak than they projected in October:

UK Interest Rates

Monetary policy (involving interest rates and money supply) is subject to significant and variable lags, typically taking at least 18 months before an action is felt in the economy. So the possibility of policy error – either tightening too much or not tightening enough – is high.

If interest rates go up too much, there is a risk of impacting leveraged businesses and countries that are heavily indebted due to pandemic borrowing.

Recession risk?

As the recent IMF report sets out, global economic prospects have deteriorated. The Ukraine crisis has negatively impacted growth potential but has also added to inflation as food & fuel prices surge. However, markets are still expecting a slowdown rather than a recession. The underlying earnings projections for large multinational companies are still fairly strong and dividends are still expected to grow albeit less quickly that in the recent post pandemic bounce. Hence the stock prices of those companies with resilient earnings and dividends are likely to find support, whereas overhyped tech companies with little or no profits will continue to struggle.

Investing in a time of inflation

The recent spike in inflation may mark the beginning of a new inflationary era, but, equally, strong deflationary forces may re-emerge. The most likely scenario is that, after the initial spike, we will experience moderate inflation at levels closer to the decade preceding the 2007-8 financial crisis than the low inflation decade that followed.

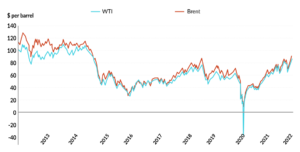

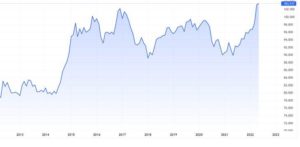

The world has shifted from a deflationary environment to an inflationary environment rapidly since the start of 2020. It is worth remembering that only two years ago oil prices fell briefly below zero.

10 year oil price chart – Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI)

Although inflation presents a threat to investors, there are specific investments which offer protection. Cash may seem more attractive with rising interest rates, but once inflation is factored in, the real return on cash is negative. Meanwhile, most bonds face the risk of further price falls as interest rates and inflation rise.

Our strategy for dealing with inflation focuses primarily on two key asset classes:

- Equities: profitable multinational companies with specific characteristics.

- Alternative assets: renewables and infrastructure projects offering inflation protected returns.

Considering these in more detail:

Equities

An environment of rising inflation and tightening interest rates is undoubtedly challenging for most asset classes, and equity markets are no exception. Equities in the advanced economies can’t escape pressure, but in the current environment, emerging markets will face far greater headwinds.

Emerging economies are experiencing two sources of pain in the form of higher interest rates and an appreciating US dollar. (The US dollar is rising partly due to those higher US interest rates but also because the dollar is considered a safe haven in times of economic stress.)

10 year chart of US dollar currency index (USD vs a basket of currencies)

The crux of the problem is that many emerging economies borrowed significant sums from the US during the pandemic and are required to pay back their debts in US dollars (becoming more expensive) at higher and higher interest rates.

Suffice to say, that narrows the investment universe down to the developed markets. The next consideration is valuation. You will recall that certain sectors of the US market, notably the tech sector, seemed to defy gravity during lockdown. In 2020, we were concerned that the boom in tech stocks was unsustainable, and in the last six months, we have seen the exuberance unwind substantially. Ultra low interest rates were one factor pushing tech stock prices higher, combined with excess liquidity as governments and central banks threw vast amounts of cash at the financial system. This effect is now running in reverse. The recent market conditions have brought down the excessive valuations in the US, but markets are still highly valued relative to the rest of the world. By comparison, equity markets in Europe and the UK, specifically, are priced more reasonably.

Within equities, we continue to invest in well managed multinational companies with strong brands and loyal customers. These companies maintain strong competitive positions in their sector and are ideal investments in an inflationary environment, particularly when the products or services they sell represent a relatively small proportion of their customer’s spending. They have pricing power, and they tend to have higher profit margins than their peers, meaning they can absorb rising input prices and raise their own prices by less than inflation and still remain profitable. The businesses tend to be ‘asset-light’, where capital expenditure and inventory requirements remain low relative to cash generation. Lastly, they maintain strong balance sheets and low levels of debt, which helps protect again the rising cost of debt as interest rates rise.

In difficult economic environments, firms with this kind of strength are able to gain market share from weaker competitors. They will produce significant cash flow to protect against inflation while proving resilient due to their competitive advantages, loyal customers and balance sheet strength.

Alternatives

The equity strategy set out above is balanced and underpinned by investment in alternatives. The sectors which will benefit the most over the next few decades are renewables & infrastructure. There is massive, planned government spending into this asset class, which offers attractive inflation-linked returns.

There is a global race afoot to decarbonise the economy, and the impact of the Ukraine crisis on energy prices has only served to accelerate efforts, especially in Europe. A new analysis from McKinsey & Co estimates that the investment in new infrastructure and systems needed to meet international climate goals will cost $9.2 trillion a year until 2050. This is $3.5 trillion a year more than the world is currently spending on low carbon and fossil fuel infrastructure and changes in land use. The expectation is that coal use will be almost eliminated by 2050, and oil and gas production will drop by 55% and 70% respectively. In the labour market, 200 million new jobs would replace 185 million redundancies in traditional sectors. There are enormous opportunities in this transition.

The report summaries the opportunities as follows:

“The opportunities for countries, sectors, and companies could be considerable if they are able to tap into growing markets as the world transforms to a net-zero economy. Nations that have abundant natural capital, such as more hours of sunshine, or that invest in technological, human, and physical capital could well be positioned to prosper in the net-zero economy. Companies could also gain from three categories of opportunity:

first, through decarbonizing processes and products, which can make them more cost-effective in some cases or tap into new markets for relatively lower-emissions products;

second, from entirely new low-carbon products and processes that replace established high-carbon options, for example carmakers meeting new demand for electric rather than ICE (Internal Combustion Engine) vehicles; and

third, through new offerings to support production in the first two categories. These could take the form of inputs such as lithium and cobalt for battery manufacturing, physical capital such as solar panels, and an array of technical services from forest management to financing to emissions measurement.”

“The net-zero transition: What it would cost, what it could bring” McKinsey Global Institute, 25 January 2022.

Summary

Although this is a time to be exercising caution, we remain disciplined, adhering to our long term investment philosophy. In the midst of a storm, it is important to remain focused on the horizon. It is worth repeating a phrase which is particularly apt in the current circumstances; “Bad companies are destroyed by crises; good companies survive them; great companies are improved by them.”

Overall, our portfolios are well diversified and designed to reduce volatility. Exposure to resilient multinational companies is balanced by investment in renewables and infrastructure which offer inflation-protected returns in a sector which is due to receive unprecedented levels of investment over the coming decades.

We are thrilled to have joined

We are thrilled to have joined